Development research donors are obsessed with achieving research impact and researchers themselves are feeling increasingly pressurised to prioritise communication and influence over academic quality.

To understand how we have arrived at this situation, let’s consider a little story…

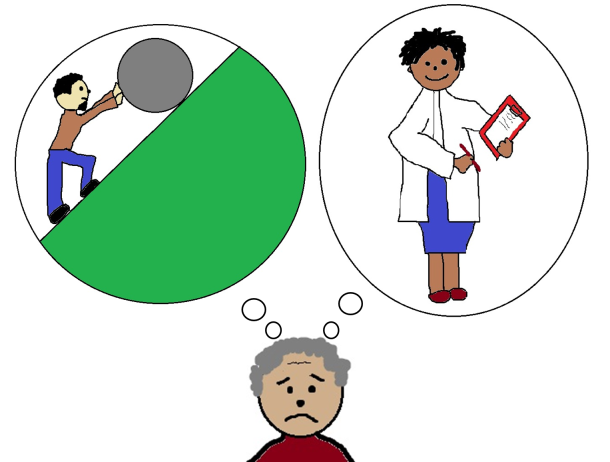

Let’s imagine around 20 years ago an advisor in an (entirely hypothetical) international development agency. He is feeling rather depressed – and the reason for this is that despite the massive amount of money that they are putting into international development efforts, it still feels like a Sisyphean task. He is well aware that poverty and suffering are rife in the world and he wonders what on earth to do. Luckily this advisor is sensible and realises that what is needed is some research to understand better the contexts in which they are working and to find out what works.

Fast-forward 10 or so years and the advisor is not much happier. The problem is that lots of money has been invested in research but it seems to just remain on the shelf and isn’t making a significant impact on development. And observing this, the advisor decides that we need to get better at promoting and pushing out the research findings. Thus (more or less!) was born a veritable industry of research communication and impact. Knowledge-sharing portals were established, researchers were encouraged to get out there and meet with decision makers to ensure their findings were taken into consideration, a thousand toolkits on research communications were developed and a flurry of research activity researching ‘research communication’ was initiated.

But what might be the unintended consequences of this shift in priorities? I would like to outline three case studies which demonstrate why the push for research impact is not always good for development.

But what might be the unintended consequences of this shift in priorities? I would like to outline three case studies which demonstrate why the push for research impact is not always good for development.

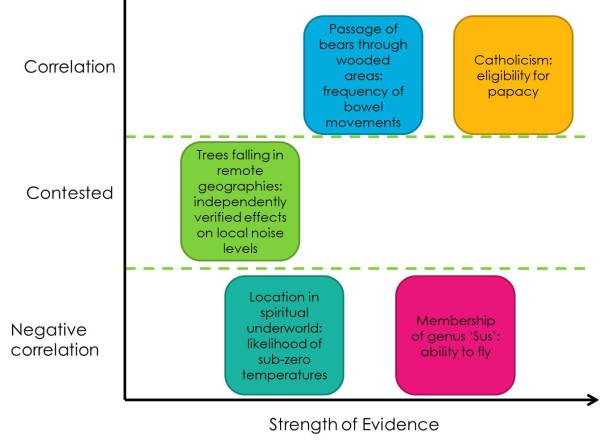

First let’s look at a few research papers seeking to answer an important question in development: does decentralisation improve provision of public services. If you were to look at this paper, or this one or even this one, you might draw the conclusion that decentralisation is a bad thing. And if the authors of those papers had been incentivised to achieve impact, they might have gone out to policy makers and lobbied them not to consider decentralisation. However, a rigorous review of the literature which considered the body of evidence found that, on average, high quality research studies on decentralisation demonstrate that it is good for service provision. A similar situation can be found for interventions such as microfinance or Community Driven Development – lots of relatively poor quality studies saying they are good, but high quality evidence synthesis demonstrating that overall they don’t fulfil their promise.

My second example comes from a programme I was involved in a few years ago which aimed to bring researchers and policy makers together. Such schemes are very popular with donors since they appear to be a tangible way to facilitate research communication to policy makers. An evaluation of this scheme was carried out and one of the ‘impacts’ it reported on was that one policy maker had pledged to increase funding in the research institute of one of the researchers involved in the scheme. Now this may have been a good impact for the researcher in question – but I would need to be convinced that investment in that particular research institution happened to be the best way for that policy maker to contribute to development.

My final example is on a larger scale. Researchers played a big role in advocating for increased access to anti-HIV drugs, particularly in Africa. The outcome of this is that millions more people now have access to those drugs, and on the surface of it that seems to be a wholly wonderful thing. But there is an opportunity cost in investment in any health intervention – and some have argued that more benefit could be achieved for the public if funds in some countries were rebalanced towards other health problems. They argue that people are dying from cheaply preventable diseases because so much funding has been diverted to HIV. It is for this reason we have NICE in the UK to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of new treatments.

What these cases have in common is that in each case I feel it would be preferable for decision makers to consider the full body of evidence rather than being influenced by one research paper, researcher or research movement. Of course I recognise that this is a highly complicated situation. I have chosen three cases to make a point but there will be many more cases where researchers have influenced policy on the basis of single research studies and achieved competely positive impacts. I can also understand that a real worry for people who have just spent years trying to encourage researchers to communicate better is that the issues I outline here could cause people to give up on all their efforts and go back to their cloistered academic existence. And in any case, even if pushing for impact were always a bad thing, publically funded donors would still need to have some way to demonstrate to tax payers that their investments in research were having positive effects.

So in the end, my advice is something of a compromise. Most importantly, I think researchers should make sure they are answering important questions, using the methods most suitable to the question. I would also encourage them to communicate their findings in the context of the body of research. Meanwhile, I would urge donors to continue to support research synthesis – to complement their investments in primary research. And to support policy making processes which include consideration of bodies of research.